Pfizer Executive Outlines Vision for Treating Sickle Cell Disease, Other Rare Diseases

Written by |

Consumers may know Pfizer as the company that manufactures Viagra, but the New York-based pharma giant is investing millions in developing potential treatments and gene therapies for rare disorders ranging from sickle cell disease and hemophilia to ALS and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Michael Wajnrajch, MD, is senior medical director for Pfizer’s Rare Disease Group and pediatric endocrinologist on the faculty of New York University. Wajnrajch outlined his company’s vision for gene therapies at the 2nd International Congress on Advanced Treatments in Rare Diseases, held March 4-5 in Vienna, Austria.

“Sometimes we’re doing the right thing for the right reasons, and it’s not about the money,” he told some 100 delegates. “Sickle cell disease predominantly affects patients with very limited ability to pay. We’re not going to make much money on this, but we know it’s an unmet medical need in many parts of the world.”

Wajnrajch, who describes himself as “a drug company executive who still sees patients,” said that even half a century since Alabama’s infamous Tuskegee experiment— a 40-year study in which the U.S. government intentionally gave 399 syphilis-infected black men useless placebos like aspirin and mineral supplements instead of penicillin — suspicions still linger.

“We can come up with a treatment for SCD [sickle cell disease] but the African-American community doesn’t want to talk to us,” he said. “Even doing even a simple clinical trial is difficult, where Caucasians wouldn’t have had a problem. This sometimes means going to parts of the world where they don’t always do clinical trials — and the FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] and EMA [European Medicines Agency] don’t like that.”

In a subsequent interview with Bionews Services, which publishes this website, Wajnrajch explained why research in sickle cell disease (SCD) is so difficult.

“For a lot of reasons, the African American community is distrustful of the medical community in general,” said Wajnrajch, who’s been with Pfizer for the past 15 years. “Tuskegee was one of the worst examples, but not the only one. Historically, it’s been a bad relationship because of the lack of trust.”

Wajnrajch added: “To this day, African Americans are typically diagnosed later than Caucasians, less often treated for standard conditions so they’re more likely to die of chronic renal failure. They’re rarely included in clinical trials, which are disproportionally male and Caucasian. So there’s a lack of interest in partnering.”

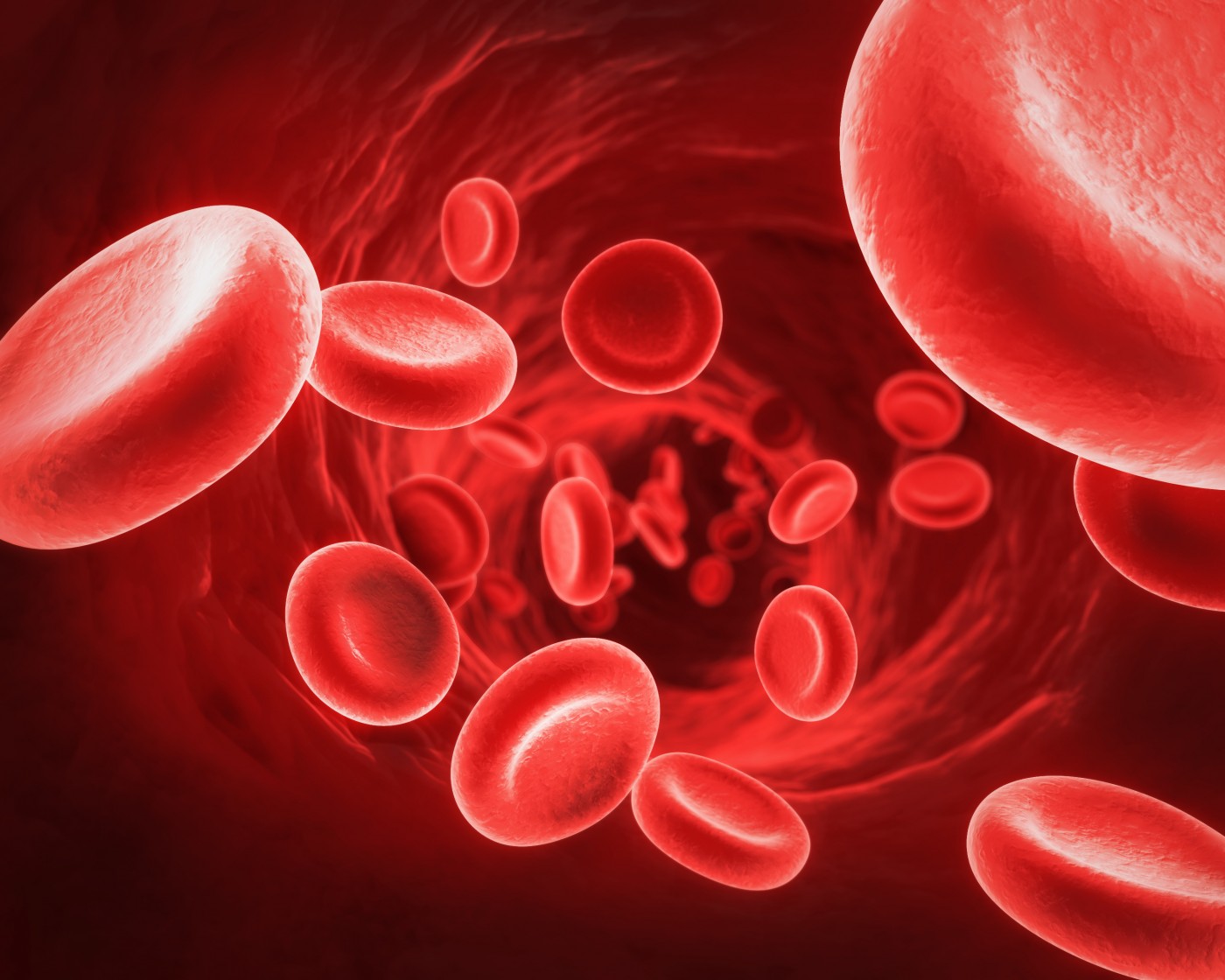

Pfizer, in a partnership with GlycoMimetics, is now a conducting Phase 3 clinical trial (NCT02187003) for Rivipansel (GMI-1070), a pan-selectin inhibitor that treats the excruciating pain of vaso-occlusive crisis associated with SCD. The trial is still recruiting up to 350 participants.

Potential in other diseases

Last year, Pfizer launched oneSCDvoice, a collaborative digital platform aimed at lending emotional support to and educating people with sickle cell disease.

Developed with help from SCD patients, advocates and medical experts, oneSCDvoice offers access to disease education from multiple sources and information about clinical trials. It also includes an online social wall for community conversations.

Wajnrach said about 3,000 of Pfizer’s 100,000 employees are involved in rare disease research.

“The gene therapy people are looking at potentially 30 areas to move forward,” he said. “But it’s very early in the process, so Pfizer doesn’t particularly talk about it.”

With 2018 revenues of $53.6 billion, Pfizer ranks as the nation’s second-largest drug company, right behind Johnson & Johnson. Rare diseases still account for a relatively small share of Pfizer’s activities, though that share is growing.

“We’re trying to think outside the box,” Wajnrajch said. “Four out of five of the 7,000 known rare diseases have an identified genetic basis, and 50% are monogenic, meaning that a single gene mutation causes the disorder. That means it’ll be easier to tailor the treatment.”

Pfizer also is pursuing gene therapies in hemophilia and Duchenne MD — two very different diseases.

“We have the capability to discover, develop and commercially produce AAV [adeno-associated virus] gene therapies. We’re investigating highly specialized potentially one-time gene therapies using custom-made AAV vectors to deliver treatments to targeted cells,” he said, clarifying that “this is not CRISPR. We’re not modifying the genes you were born with.”

Of all rare diseases, hemophilia is the farthest along when it comes to gene therapy in general, though he said the AveXis drug Zolgensma (AVXS-101) also shows huge potential to cure SMA. Yet, other diseases like Duchenne are more tricky.

“When you want to cure hemophilia, you give the vector and it goes right to the liver. When you want to fix DMD, you need to reach every muscle in the body,” he said. “That’s a problem, because you can’t inject one little thing and get it right. Companies can make enough to treat a patient to see a sign of efficacy, but it’s not a commercial cure.”