Georgia Universities Join NIH-funded National Study of Bone Marrow Transplant for SCD

The Medical College of Georgia (MCG) and Augusta University Health (AU Health) have joined the first large, national clinical trial investigating bone marrow transplantation as part of the standard of care (SoC) for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded study will conduct bone marrow transplants in patients who have high-risk SCD and who have a compatible bone marrow donor (typically a sibling, but it also can be an unrelated donor), and follow patients for whom a compatible donor wasn’t found, while giving them SoC treatment.

The objective is to compare the two groups and see which approach results in the best outcomes.

MCG is one of 20 sites actively enrolling patients from 15 to 40 years old. Jeremy Mark A. Pantin, MD, hematologist and oncologist at MCG in charge of the study, said in a press release “We want to be able to offer the option of cure to our patients who struggle the most with this chronic disease. You want to take away patients’ suffering and help them have a longer and healthier life.”

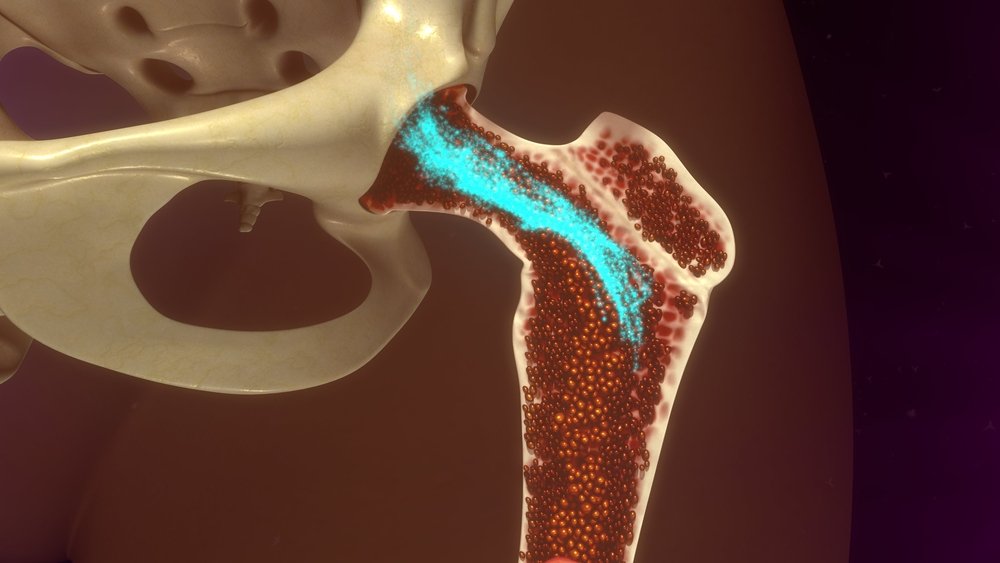

The bone marrow of SCD patients produces short-lived, red blood cells that don’t carry oxygen well enough, taking an odd, sickle shape when they release the oxygen and becoming rigid afterward. These rigid cells clog vessels and block blood flow. Patients often have pain crises, which end up leading to frequent hospitalizations.

The approach used in the trial includes eliminating the patients’ own bone marrow with chemotherapy and then replacing it with donor bone marrow given intravenously. After the transplant, patients should not spend less than two weeks in a sterile unit of a hospital, while new white cells populate and re-establish immune protection.

Patients are required to continue taking immune-suppressive drugs for another six months, to reduce the risk of graft-versus-host-disease (GvHD), because this is the time it should take for the body to learn how to recognize its new cells and refrain from attacking them.

GvHD is a life-threatening side-effect in the first year after transplant when the newly acquired immune system attacks the patients’ organs and tissues.

A sibling with identical tissue match is the preferred transplant donor, but the National Bone Marrow Donor Program also can help find an unrelated match. Participants in the study will be followed for two years.

Could benefits of bone marrow transplantation outweigh the risks? For Pantin, it’s only a matter of time until bone marrow transplants become a SoC offer to all patients with a suitable donor. Even though evidence suggests that transplants tend to work best in children with less developed immune systems, Pantin believes that with careful selection, adults can benefit from it, too.

“Selection is critical,” Pantin said. “You have to balance the patients’ complications through the course of their illness and the reality that patients generally have a reduced life expectancy, with the promise of being cured of the disease but not without some risk.”

Pantin said that to participate in the study patients must have experienced at least one of the most serious side effects known to SCD, including a stroke, at least two episodes of acute chest syndrome in the two previous years, or three or more pain crises per year in the previous two years. Patients with a history of substance abuse, who are pregnant or breastfeeding, or who had an uncontrolled infection in the six weeks before enrollment will be excluded.

For more information about the study, contact Leigh Wells or Latanya Bowman at (706)721-2171.