Higher Risk of Upper GI Bleeds in SCD, Study Finds

People with sickle cell disease (SCD) have a higher risk of bleeding from the upper portion of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, possibly due to the use of certain anti-inflammatory medications and stress brought on by frequent hospitalizations, a study has found.

The study, “Bleeding in patients with sickle cell disease: a population-based study,” was published in the peer-reviewed journal Blood Advances.

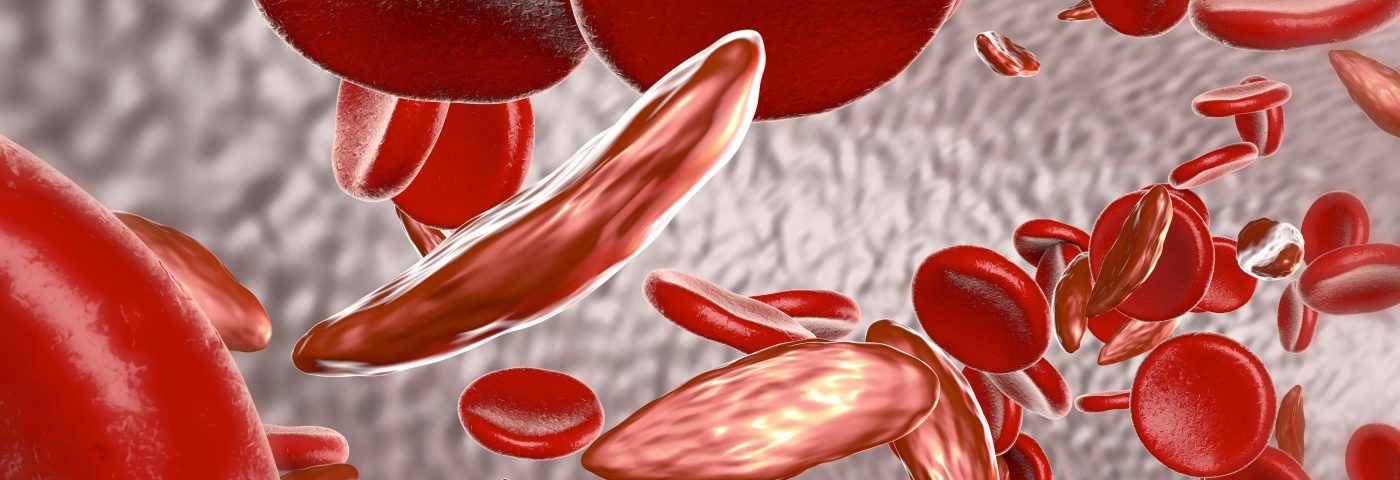

SCD is caused by a mutation in the hemoglobin (HBB) gene. This mutation causes red blood cells to adopt an abnormally curved, or sickle-like shape, which makes them rigid and less able to circulate through small blood vessels. That results in poor oxygen delivery to the body’s tissues, leading to episodes of pain and inflammation known as pain crises.

This temporary blockage and return of blood flow, known as vascular occlusion and revascularization, is thought to underlie the bleeding episodes that people with SCD experience.

“Although patients with SCD can experience multiorgan site bleeding, existing reports primarily focus on organ-specific bleeding. To our knowledge, the burden of all bleeding events and association with mortality in patients with SCD have not been reported,” the researchers said.

To learn more, a team of scientists at the University of California reviewed records from hospitals and emergency room department databases within their state to identify people with SCD who had experienced bleeding events.

From 1991 to 2014, 6,423 SCD patients in California were identified. Among them, 1,345 (20.9%) had at least one bleeding occurrence. GI bleeding was the most frequently observed first bleeding event, seen in almost half (41.6%) of the individuals.

The mean age at which patients had their first bleeding episode was 32.9, and the two most common bleeding incidents among all individuals were GI bleeds and menorrhagia, or a heavy menstrual bleed. With the exception of menorrhagia, a patient’s sex did not seem to influence anyone’s risk of having a bleeding event.

Instead, the researchers found that specific locations within the GI tract appeared to be strongly linked to these bleeding episodes. Indeed, in more than half (60%) of the patients with a first-time GI bleed, there was involvement of the upper portion of the GI tract.

Having an initial bleeding event also was strongly associated with further episodes, the researchers found. Overall, 24.8% of patients who had an initial bleeding event later had another event in the same location. This pattern was seen in 35% of those with menorrhagia, 32% with GI and ophthalmic (eye) bleeds, and 9% with intracerebral hemorrhage, known as ICH.

The investigators also identified several risk factors associated with bleeding events. More than a third (30.5%) of patients who had been frequently hospitalized were found to experience a bleeding event by age 40, whereas only 12.6% of those with less frequent hospitalizations had the same outcome.

Frequent hospitalization increased the risk for bleeds of any kind, as did a venous thromboembolism, or VTE — a blood clot that forms in a deep vein, usually in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis —within 180 days of the first bleeding event. However, a VTE occurring more than 180 days after the first bleeding was not associated with an increased risk of bleeds, the study found.

In addition, patients who had prior ischemic strokes — the most common type of stroke, occurring when a vessel supplying blood to the brain is obstructed — were more likely to later experience an ICH.

Such hemorrhages, and to a lesser extent GI bleeds, were both associated with greater risks of mortality. ICH had an in-hospital mortality rate of 24.7% and GI bleeds of 5.68%. Mortality risks were not increased for menorrhagia, ocular bleeding, or hematuria (bloody urine).

Altogether, people with SCD had a more than four-fold risk of experiencing upper GI bleeds, and a three- to five-fold risk of having lower GI bleeds, compared with the general population, the study found.

In addition to tissue damage caused by vascular occlusion and revascularization, the investigators noted that frequent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) might make patients more susceptible to ulcers and other upper GI bleeds. Further, the stress of frequent hospitalizations also might be another contributing factor in ulcer-related GI bleeds.

The researchers called for possible preventative treatments for people with sickle cell disease who need hospitalization.

“This raises consideration of empiric ulcer prophylaxis for all hospitalized patients with SCD, as well as attempts to minimize usage of NSAIDs whenever possible,” the researchers said.

“Furthermore, the significant association of a prior ischemic stroke with future hemorrhagic stroke warrants further study on the temporality between the two, as well as investigation into possible preventive measures,” they said.