Health Improves After Stem Cell Transplant, But Challenges Remain

Patients surveyed said they felt empowered to play sports, travel, get a job

Written by |

People with sickle cell disease (SCD) may see their physical, mental, and social health get better after a stem cell transplant, and this may help them pursue their personal life goals, a small study found.

Still, challenges remained as they “confronted a new and unfamiliar reality,” the researchers wrote in the study, “Physical, Mental, and Social Health of Adult Patients with Sickle Cell Disease after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Mixed-Methods Study,” which was published in Transplantation and Cellular Therapy.

These included emotional struggles and feeling overwhelmed. The researchers said to address this, doctors “should aim at creating realistic expectations before transplantation and offer timely psychological care.”

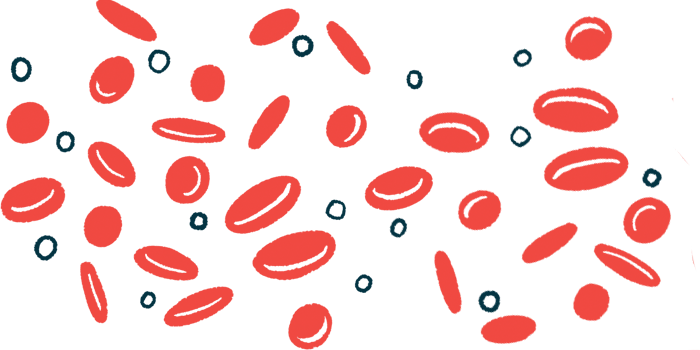

People with SCD have abnormally shaped red blood cells that don’t live as long as healthy ones. They’re also stickier, making them more prone to blocking blood flow throughout the body.

This can cause a range of symptoms, from painful episodes — known as vaso-occlusive crises, or VOCs — to recurrent infections and anemia, which occurs when there aren’t enough red blood cells to carry oxygen to tissues.

The only cure is a stem cell transplant, a procedure that destroys a patient’s bone marrow cells to make room for stem cells harvested from a healthy donor. Stem cells can give rise to different types of blood cells, which means the unusually shaped red blood cells can be replaced by healthy ones.

While having a stem cell transplant may make for a better quality of life, “preceding expectations of living a healthy life might influence the perception of success or failure of the treatment,” the researchers wrote. “A thorough understanding of the physical, mental, and social health before and after being cured is necessary to meet the needs of this growing group of patients.”

Transplant was ‘hard, but worth it’

Researchers in the Netherlands studied the perspectives of adult SCD patients on the changes they experienced after a curative stem cell transplant.

They interviewed 10 people, ages 19–49, who’d had a stem cell transplant a median of 2.7 years before at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, the Netherlands. Only one was still on immunosuppressive treatment at the time of the study. One or two researchers interviewed each patient, either face to face or via videoconference, for a mean duration of 48 minutes (ranging 30 to 70 minutes).

The interviews touched on seven areas of the patients’ lives from before, during, and after the transplant. These included pain, physical and mental well-being, outlook, education or work, family and friends, and participating in activities.

From the interviews, it became clear SCD affected all aspects of physical and mental health.

“I just was someone that was sick very often,” one patient said. “I was, to put it briefly, basically traumatized by it [SCD].”

The disease also took a toll on their social health, with patients feeling restricted from engaging in social activities and sports, such as swimming, cycling, and fitness.

In the year after the transplant, most described the process as “hard, but worth it.” Many said they had side effects, such as fever, headache, skin changes, hair loss, bowel disturbances, irregular menstrual periods, and weight gain.

While they’d been informed about the problems that might arise during or after a transplant, the problems “often came as a surprise,” the researchers wrote.

At the time of the study, two patients had pain from avascular osteonecrosis, which occurs when bone tissue dies due to a lack of blood supply. Three others continued to have fatigue, despite having a normal red blood cell count.

While some saw their mental health improve, others saw emotional struggles and expressed a need for psychological help.

In spite of that, most patients saw their social health improve.

“The transplantation was not only of benefit for myself, but also for my family. I would have done everything to not have crises anymore and take that powerless feeling from them,” one patient said.

The transplant also gave patients the opportunity to pursue their personal life goals, from taking up sports to getting a driver’s license or job, buying a car or a house, or even traveling.

“I noticed that when I was cured it felt like a whole new world opened up to me, so I wanted to do everything all at once,” one patient said.

Researchers also used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to look at nine measures of physical, mental, and social health. Measures are expressed in T-scores, which are standard scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 in a reference population.

Despite some variation, mean T-scores for all PROMIS measures fell within the normal limits compared with the reference (general) population. Half the patients scored within normal limits on eight or all of the PROMIS measures.

In general, patients saw better physical, mental, and social health after a stem cell transplant. Still, researchers said patients should be aware of the issues that might arise after a procedure.

“Regardless of whether this reality measures up to their expectations or is valued as an improvement, they face challenges that call for awareness,” the researchers wrote. “Clinicians can use the insights gained from our and other studies to recognize the needs of SCD patients undergoing curative treatments, manage their expectations beforehand and to install SCD patient-tailored pre- and post-transplantation psychological care.”