Expert Analysis Updates Advice on Managing Sickle Cell Retinopathy

Following a review of studies published in the last decade, experts have updated their recommendations for managing a sickle cell disease-related eye complication known as sickle cell retinopathy (SCR).

Their paper, “Sickle cell retinopathy: improving care with a multidisciplinary approach,” appeared in the Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare.

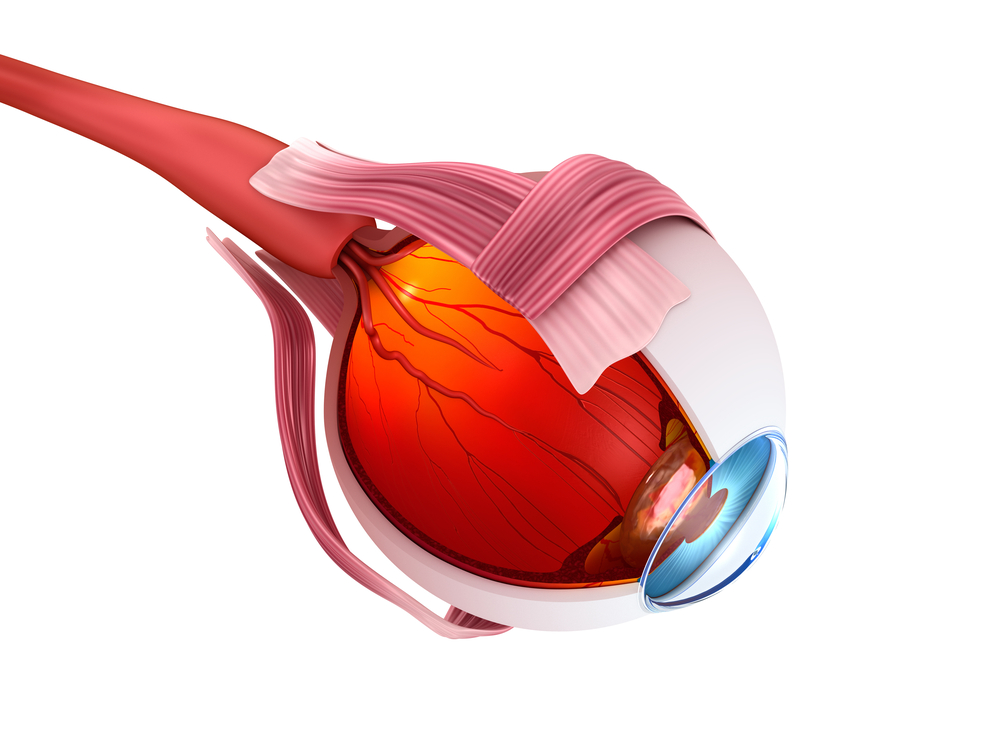

SCR, a condition characterized by damage to the retina, is caused by sickle cell disease (SCD). If left undiagnosed and untreated, it may lead to irreversible vision loss.

The authors reviewed articles published between 2007 and 2017 to update tools for diagnosing and improving SCR patients’ outcomes.

While healthcare measures in the last decades have significantly increased SCD patients’ life expectancy, clinicians have witnessed a rise of ocular complications due to SCD. As such, authors recommend that retinal examinations be done in all SCD patients.

The authors extend this recommendation to those with sickle cell trait (SCT) when these individuals present signs of systemic vascular problems. People with SCT usually do not have any of the symptoms of SCD, as they inherited just only one sickle cell gene and the second one is normal. In order to detect signs of retinal lesions and visual impairment, SCD patients should be screened from early childhood.

“In addition to patient screening and complete eye examination, it would be helpful for the health care professional to earlier assess the presence of factors and biomarkers that increase the chance of developing proliferative sickle cell retinopathy (PSCR),” authors wrote.

In SCD patients, being male, having pain and presenting splenic sequestration — when many sickled red blood cells become trapped in the spleen — are clinical risk factors that signal the need for a thorough eye exam, authors noted.

Systemic factors, such as high levels of hemoglobin, are likely linked to PSCR in sickle cell patients. Authors added that, “to date, overall reports showed that the prevalence of PSCR increased mainly with age (over 35 years) and with systemic severity (i.e., inflammation), particularly in SC genotyped [DNA sequence examined] patients.”

Significant improvements in therapies over the last 20 years have extended the life expectancy of children with SCD.

Conventional therapies for SCR include chemotherapy and phlebotomy (drawing blood) in conjunction with long-term blood transfusions. Severe cases are often treated with laser-mediated photocoagulation and surgery. Although used less often, alternative and complementary therapies such as hyperbaric (elevated pressure) oxygen therapy (HBOT) and gene therapy are also available. In HBOT, patients receive 100 percent oxygen in a pressurized chamber.

A preventive treatment strategy for SCD, due to its safety and efficacy profile, is hydroxycarbamide, often known as HU.

“HU therapy is strongly recommended for SCD adults with at least three severe vaso-occlusive crises during any 12-month period, with pain or chronic anemia interfering with daily activities, or with severe or recurrent episodes of acute chest syndrome,” researchers suggested.

Additional therapies may include anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy. Iron-chelation therapy in patients with SCR presenting hemochromatosis (iron overload) may also be recommended, with caution. Many patients with SCR may also be eligible for preoperative transfusion therapy to increase their hemoglobin levels.

In the future, the development of animal models mimicking the human features of SCR will help scientists better understand the causes and mechanisms leading to the disease, authors concluded.