Better outcomes with lactated Ringer’s in vaso-occlusive crises

Fluids lost in sickle cell disease pain episodes are usually treated with saline

Written by |

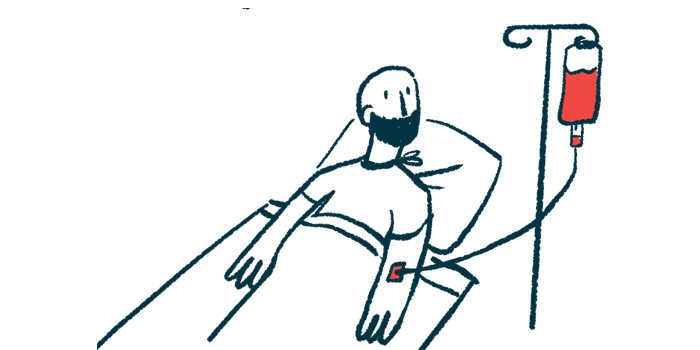

Using lactated Ringer’s solution instead of normal saline to replace lost fluids in adults admitted to the hospital for vaso-occlusive crises, that is, pain episodes caused by sickle cell disease (SCD), allows for shorter stays, fewer readmissions, and a reduced need for opioids, a study finds.

Dehydrated sickled red blood cells have more concentrated sickle hemoglobin, the faulty protein in SCD, making them more likely to stick to and block blood vessels, causing pain. Normal saline is often used in clinical practice to treat dehydration because it’s easy to get, but it may worsen sickling.

“Our results provide strong evidence that a change in standard practice is needed,” Nicholas Bosch, MD, an assistant professor at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, said in a university press release. Bosch, a pulmonologist, critical care physician, and health services researcher at Boston Medical Center who led the study, said “switching from normal saline to lactated Ringer’s will not only improve outcomes for our patients, but also potentially lower healthcare costs.”

The study, “Lactated Ringer vs Normal Saline Solution During Sickle Cell Vaso-Occlusive Episodes,” was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Sickle hemoglobin, a faulty version of the protein that carries oxygen in red blood cells, clumps into rigid threads that bend red blood cells into a sickle-like shape. These misshapen blood cells tend to stick to the lining of blood vessels, blocking blood flow, and depriving tissues of oxygen, a process that can lead to vaso-occlusive crises.

Patients admitted to the hospital for these episodes are often given normal saline, a solution that contains water and 0.9% of sodium chloride, to make up for low blood volume, even though some studies suggest saline may increase red blood cell sickling.

Comparing lactated Ringer’s, normal saline after pain episodes

To see if lactated Ringer’s, a balanced solution of water, sodium lactate, and other salts at levels similar to those in blood, could be better than normal saline, Bosch’s team drew from a database that includes information about 25% of the hospitalizations in the U.S. from 2016 to 2022. The study included data from 15,798 patients, ages 25-37, who had 55,574 hospitalizations for vaso-occlusive crises. Normal saline was administered to patients on their first day in the hospital in 52,079 hospitalizations, while lactate Ringer’s was administered in 3,495.

When researchers compared hospital-free days, a measure of how many days patients stayed out of the hospital in 30 days, they found those who received lactated Ringer’s had more hospital-free days than those given normal saline.

Patients treated with lactated Ringer’s also had shorter hospital stays, more intravenous (into-the-vein) opioid-free days, and a 5.8% lower risk of being readmitted to the hospital within 30 days than those treated with normal saline.

When researchers looked at how much fluid was administered, they found that for patients who received less than 2 liters, there was no significant difference between lactated Ringer’s and normal saline. However, for those who received 2 liters or more, lactated Ringer’s worked better.

“Currently, patients with sickle cell disease who are admitted to the hospital for vaso-occlusive pain episodes usually receive normal saline and clinical decision support tools presently recommend normal saline. However, our results call these recommendations and current practice into question,” Bosch said.

“The more fundamentally we understand the science of sickled erythrocytes and fluid resuscitation, the closer we can come to understanding which interventions are most effective, when, and for whom, in both low- and high-resource settings,” scientists from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore wrote in an editorial that accompanied the study. “Ultimately, patients living with SCD may have more days outside of hospital care to chart their own journeys.”